“Every figure is a world, a portrait whose subject appeared in a sublime vision, bathed in light, revealed by an inner voice, as a celestial finger laid bare the sources of expression in the past of a whole life.”

H. Balzac, A obra-prima desconhecida [The unknown masterpiece], p. 38

Though Balzac’s intention was never to describe some kind of metaphysical depiction of works of art, the above text nonetheless contains one of the most powerful descriptions of art’s demon (in the Greek sense of daemon), an entity which hails from a plane that does not circumscribe itself to materials, objects, or purely sensitive experiences. This plane goes beyond mere data: a purely sensitive experience is not enough for it, and it peculiarly tends to exorbitate. Even though, as Kant well acknowledges, such is the tendency or natural vocation of human reason, in artistic terms there is a risk of annulling the work of art, the figure, the colour patch, the object itself.

In the same text, Balzac tells us the following, through the lips of the master painter who insists on not revealing his work to his friends: “The picture I keep upstairs under lock and key is an exception in our art; it is not a canvas, it is a woman!” This metamorphosis of painting into flesh, of artistic material into the material of life, is not exempt from danger, being a supremely confusing realm, where things do not seem what they are and are not what they seem. This feeling of distrust generates aesthetic discomfort: it is as if every work of art were concealing a kind of malignant genie who is constantly trying to delude us with perceptive tricks, keeping us from taking the things’ apparent nature for granted. But the reasons for mistrust become reasons for praise: a crown of thorns and of glory. It is like when Plato, in the Republic, lists the reasons for keeping artists out of his city and his damning speech becomes one of the most beautiful exhortations on the powers of art. In other words, this genius may be indeed malignant, but is also at the same time a creative entity, which carries the power of configuring matter into symbol, sign, experience, knowledge.

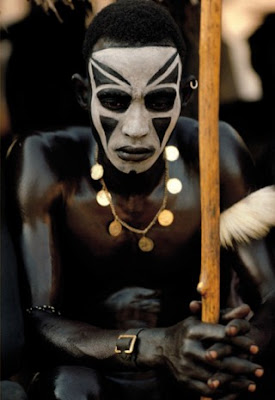

Balzac’s formulation implies something that many misunderstand and find unjustified: that the work of art cannot be just another object, that it must be a mould, a model, a portrait – a world, in Balzac’s words. Besides being a moral imperative, it demands a kind of relationship with the world that finds its finest expression in the concept of figure. The relationship between the figure and the world, which must be explored here, corresponds to the effort of making something visible, an effort that incorporates both the amazement at the fact that things exist and the amazement at their being as they are. The arts thrive on serving such amazements.

The approach that characterises those who envisage aesthetically qualified objects as moments of contemplation implies avoiding any unnecessary, fortuitous, ungrounded gestures, any randomly-traced arabesques. The relationship of the figure with the world implies the acknowledgment of something as characteristic and proper; hence, the world is its place of resonance. It is concerned with turning the world into something identifiable, or, in other words, with the painstaking organisation of the visual field.

This relationship is not about strict representation – to represent is to play a part: to be in the place of…, to use a mask to look like… –, being instead a place of discovery. Just as names are nothing more than keys for entering into things, figures are gestures that, on a formless, indeterminate background, are able to delimit, recognise, and intuit areas for communal exchange.

According to Jünger, “«Intueor» is a verb the Ancients only knew in its passive tense and through its causes. Naming would only come later: things do not carry their own names, they are conferred upon them. The world of names is different from the world of images: it is nothing more than a reflection.” (Typus, Name, Gestalt, §24)

The figure is thus the presentation or, if you prefer, the materialisation of intuition: on the paints on a canvas, on the lines of a drawing, on the wood or iron of a sculpture. And the ancient meaning of intuition – the fact of being affected, impressed by something – puts the configurative activity of the human mind on hold, briefly turning all knowledge into acknowledgment. This praise of a certain passivity of the individual leads to a relationship of discovery of that which emanates from the things themselves. It is as if, from this point of view, interest resided in the sight – and to intuit is, in some way, a form of sighting – of the things themselves, in their most chaotic, shapeless, disorganised forms, untouched by rationality or integration into the systematic mind, that is to say, intuition as a contact with the before-the-name, as something sighted under the midday sun, without shadows, without filler. Jünger tells us that names are reflections, shadows of things, human acts; while images are closer to the source. And the image, here, is the figure-being of what is seen: let your body cast light and shade so that I may see you, so that I may recognise you, so that you may be.

“The conception of the figure presupposes the human being, as a spirit that conceives, but also as a spirit that engenders. A new element enters man, to be named by him and thus known, but also recognised.” (Jünger, op. cit., §113)

This spirit that engenders, who is, where the construction of the figure is concerned, the artist, works on the threshold of discursiveness, that is to say, as it engenders it is itself engendered: I am what I see and what I see is me. To allow oneself to be entered by that new element means not only to recover intuition, but is also the condition for the formation of figures: it means to simultaneously create the world and oneself, with one’s body becoming the medium for the birth of the new, the place of the unexpected, the place of revelation. The figures thus engendered correspond to the tension of differentiating the undifferentiated: the patch, the figure’s prime mover and first perceptive sign, displays the effort of knowing and sorting out the formless. It has to do with tearing a name out of what is nameless, tearing a figure out of what is indistinct: “every image, every phenomenon in its imagistic and symbolic language, is a case apart, a delimitation from the undifferentiated” (Jünger, op. cit., §108). This delimiting action amounts to the discovery of the individual, of the singular, of the unique, to the birth of multiplicity. Only out of confrontation with multiplicity can emerge the unity of the singular case, and only through confrontation with heterogeneity one can become aware of oneself: at the limit, the figure is a variation of that same undifferentiated.

But the figure is simultaneously a synthesising movement, and hence a world: its finest presentation is the human body, which is not only the mediator par excellence of all figures, but also their source and destination. In the words of Filomena Molder: “the works themselves ask, suggest and demand a certain movement, a certain mood form their contemplator, which appears only in the most depurated sense, in relation to the work’s spatial essence, that is to say, in relation to the place of the space consistent with the contemplated work. It is always a matter of the work’s demands, never of point of view” («Notas de leitura sobre um texto de Walter Benjamin», Matérias Sensíveis, p. 19). Work and figure are somewhat equivalent here, because we believe that the figure is a work. The “place of the space” is a consequence of the figure’s irruption: its birth corresponds to an inaugural gesture, a suspension of time and a demarcation in absolute space. The figure, like the work of art in general, is the action of making space perceptible and time sensitive. Another aspect of the proximity we are describing here is the autonomy, expressed in the form of demand, of the figure: the individual’s subjectivity is not taken into consideration; it is the figures’ demands that matter. It is them that determine the body’s place in space, the movements, the sensitive dance, on pain of, should their demands not be satisfied, sinking into profound muteness and invisibility.

Another aspect that must be highlighted is that the construction of the figure is not directed by a choice, since it is a direct response to a need for orientation: in Jünger’s fine comparison (op. cit., §88), figures are like a kind of compass that is only useful during the journey: it shows where the North is, it orients you, but does not tell which way to take.

“In the case of the figure, not only do contours tend to become blurry, but the very consciousness that faces them is less present. One approaches a deeper knowledge, closer to presentiment foreboding premonition – a kinship that lies in the nature that configures, rather than in configured nature.” (Jünger, op. cit., §128).

The abovementioned near-absence stresses the direct contact between the figure and whatever it figures, presents or represents. In comparison with language, it is known that the figure runs deeper, since it is made of the same ingredients as what it represents. That is the reason it is possible to perform transitions in which the elements fit together, instead of belying or contradict each other, and that is why Jünger says that after a while the figure’s contours tend to blur: the figure’s maximum potency corresponds to its evanescence.

Let us return to Balzac: “You are looking for a picture, and you see a woman before you. There is such depth in that canvas, the atmosphere is so true that you can not distinguish it from the air that surrounds us. Where is art? Art has vanished, it is invisible!” (Balzac, op. cit., p. 68).

It is a paradoxical situation: truth in art, like depth in the figure, amounts to its annulation: it intrudes into the facts of the world, becomes a fact of the world, a space turned conscious. The fact that the air can flow through the figure’s body is an indication that the figure’s power lies in a superior type of vision, a power that is exerted over everything that exists: there is only one power similar to this one: the power of naming. The fact that the figure does not appear in the universe, that it cannot be taken and integrated into a unifying discourse, means that the figure is the prime manifestation of that same universe: it is a matter of transforming cosmic and metaphysical power into tangible, sensitive, measurable reality, part of the field of vision and perception.

“The cosmic depth and the inexhaustible depth of Man are but one: matter, spirit, prodigy, sea, forest, light, sun, desert and any other name you may wish. There are no differences or qualities there. Number, thinker, height, depth, understanding no longer mean anything…” (Jünger, op. cit., §122)

The fact that a relationship can be established between all things does not mean that everything is equal to everything: by means of human ingenuity the new takes place, the strange may happen. But the correspondence defined here concerns the possible transitions between elements, and how diversity is found in this depth shared by man and the cosmos: the multiple finds and recognises itself in the ONE. The same applies to works of art: it is possible to perceive a “genetic agreement between the orientation of the body, the movements of the hand, the direction of the artist’s eye and its effect on the one who contemplates: the picture, the drawing, the Chinese painted silk, the wall painting, the fresco all call to themselves, in metaphysical relationships, a form of looking, a place, which cannot be arbitrary” (Maria Filomena Molder, op. cit., p. 20).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Balzac, Honoré, A obra prima desconhecida, [Le chef-d’oeuvre inconnu, 1831], Lisboa: Ed. Vendaval, 2002

Didi-Huberman, Georges, La peinture incarnée suivi de Le chef d’oeuvre inconnu par Honoré de Balzac, Paris: Les éditions de Minuit, 1985

Jünger, Ernst, Type, Nom, Figure [Typus, Name, Gestalt, 1981], Paris: Christian Bourgeois Ed., 1996

Molder, Maria Filomena, Matérias Sensíveis, Lisboa: Relógio D’Água Editores, 1999

*text published in the catalog from the show "Corpo Intermitente", Museu de Angra do Heroísmo,Açores, curated by João Silvério and produced by FLAD